Rajah Rutnam (1934 – 2009) Ceylonese Pioneer First Ceylonese Migrant to the United States under the Mc Carrann Act of 1952

Rajah Rutnam (1934 – 2009) Ceylonese Pioneer First Ceylonese Migrant to the United States under the Mc Carrann Act of 1952

“I loved Ceylon, but I was ‘in love’ with the United States.”

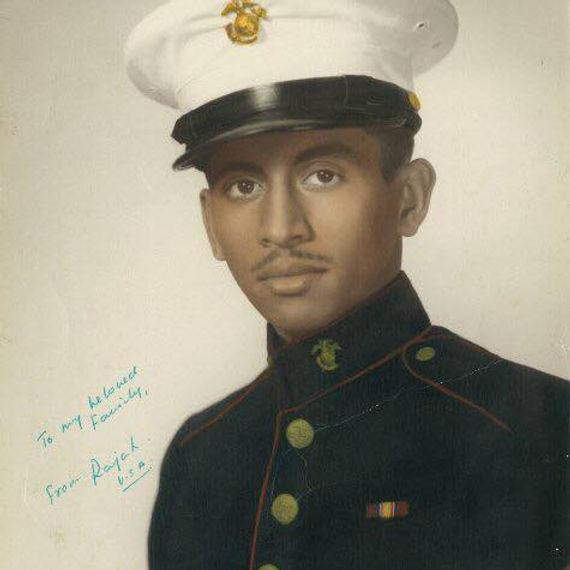

“………and I became an American” by Staff Sergeant Rajah Rutnam USMC

______________________________

In the coolness of a fresh and bright September morning in 1954, from my hotel in downtown, Los Angeles, California,

I walked to City Hall. As my anxious feet carried me through its portals I could almost hear the throb of my exuberant

heart. A rare sensation, so obvious that even the elevator boy, sensing it, smiled mirthfully as he greeted me.

I stepped out on the third floor to discover that I was not alone. There were about a hundred of us, representing many nations. With those who belonged to the same alphabetical category as mine, I took my place at the end of a long line. From this position I gazed into a sea of glowing faces, and could feel exuding from them an excitement kin to mine. There were some who endeavored to appear nonchalant, while others were anxious to share their stories with everyone.

We had been standing for quite awhile, and in my impatience I was getting rather restless. When the clerk waved us into a court room, I sighed with relief as I seated myself upon the bench to which I had been directed. I was bent over reading some pamphlets when I heard the rap of a gavel announce His Honor the Judge. The court arose in one accord. Ordinarily he might not have been considered a very impressive person, but on this day his presence was remarkably commanding. The court was seated and he began to speak. His voice projected in a mild manner, warm and friendly, commanding our fullest attention. In strange unity we listened as he spoke of the imperativeness of our understanding the change in ourselves. His clear voice relayed the full significance of his words.

The austere environment of that courtroom was the stage for a great drama. The peoples of many nations, colors and religions, sensing a kindred feeling of belonging, discarded the dark cloak of prejudice to bring into vogue the handclasp of friendship. A common perk representative of the unity that makes the United States. Together “we”, the peoples of the old worlds, rose to face the colors of the new. With the right hand raised, in the roar of a hundred voices, a hundred hearts pledged their allegiance to the flag of the United States and to what it represented.

In the calm that followed the judge looked on us gravely. “Congratulations”, he said, “You are now citizens of the United States. With new privileges you have new responsibilities. Bear them well, for in your hands you hold the freedom and the future of America. Your country”. My country America! an ‘ALIEN’ walked into a courtroom and an ‘AMERICAN’ walked out. Bursting with the sense of pride and joy which is a part of becoming an American, I stepped out into the streets of America, an American among Americans.

It seemed it was all a dream. But then, that was how it all began. A dream that no fourteen year old boy had the right to dream. But he did. The dream that was impossible had culminated in reality. Where did it begin?

In the Indian Ocean, reposing like a teardrop, off the south point of India, lies the emerald island of Ceylon. On this former British colony, in the capital city of Colombo, I was born. Reclining on her luxuriant beaches at Mount Lavinia and Negombo, often looking far beyond the horizon, I dreamed a million dreams. Dreams of youth, of adventure, of romance. I dreamed of the United States. I learned to love her and her people.

The passage of time added fuel to the fire of my very imaginative mind, and I saw an American that no one else could see. It was a very strange “romance”. I loved a country I had never seen, except in the movies, in the books I read, and in the people I met. I studied her great constitution, and believed in her ideals. Living within myself I discovered the glamor of Hollywood, the excitement of Broadway and New York and the adventure of a nation of many peoples. I loved Ceylon, but I was ‘in love’ with the United States.

In 1949, I was a resident student at St. Thomas’ College in Gurutalawa, a beautiful estate, on which I spent the exciting years of youth. There were times, when my friends and I, with the strategy of generals, invaded the school orchards, evading the caretaker, and braving Principal Hayman’s heavy cane. A campus cloaked in the blanket of natural beauty, where flowers blossomed all year round, and birds of variety sought sanctuary with the protection saint of the school chapel, St. Francis of Assisi. Here in an environment of nature’s luxuries I made a decision that affected my entire life. I decided that I would become an American.

The seeming impossibility of my ambition, made me the object of mild ridicule among the professors and students. I was subjected to the jocular criticisms of my friends and relatives. “Why don’t you give up this crazy notion?”, some would say, “you will only be disappointed”. “get yourself into reality”, said the Principal, “this obsession is a sign of immaturity”.

They might have all been right. I probably was immature, but I could not cast out my dream. With stubborn perseverance I held on. It might not have happened, if I had once said to myself that it was impossible. I prayed. In the afternoons when no one was watching, I would sneak into the chapel to say a prayer for a chance to make this dream come true. But dreams and prayers are not enough.

There was need for action, and I did not know how to begin. My mind wandered in uncertainty, till it occurred to me that my question would be well answered by the first gentleman of the United States. In a letter to the President I wrote of my ambitions, and asked him if I could become a citizen of the United States.

My letter was intercepted, presumably by the State Department, and was referred to the American Embassy in Ceylon for reply. In answer to my query the embassy stated that I had first to establish permanent residence in the U. S. to become eligible for naturalization. In turn I requested pertinent information. I was told that I had to be legally admitted to the U. S. on an immigrant’s visa. How? The Embassy regretfully informed me that at that time Ceylon had no quota for immigration to the U.S. , and to my great consternation I discovered that I could not become an American.

In spite of everything my thoughts were not restrained. I stlll believed that I would become an American. This naturally created new problems. My folks were not quite reconciled to the idea of my planning to become an American. My father’s plans for me did not include my migration to the U. S. When he questioned me, I told him of my correspondence with the American Embassy, and of the latest developments concerning a U. S. bill of law which would, if passed by Congress, make me eligible for U. S. citizenship.

The slow fuse had reached a point of detonation. My father exploded in a torrent of angry words. “Do you realize what you are doing?”, he asked, “you are selling your birthright. Many people want to make Ceylon their home, and you want to throw away your heritage for something you know absolutely nothing about”. His own sense of patriotism was great, but he could not understand why I wanted to go to the United States. For this venture he told me in no uncertain words that I could expect no help from him.

During this time, an immigration bill was under fire in the U.S., and my ‘domestic relations’ had not improved. I was working at my father’s export and import business as a junior executive, who was so junior that he was a sort of glorified errand boy. In an air of strained relationships, my resentment of this status created considerable tension at home. I was under 21 years of age and the fact that I needed my father’s consent before I could be issued a passport worried me.

All my schemes to come to the U.S. ended in failure. I had even become a candidate for a Government sponsored scholarship to the U. S. I was interviewed and eliminated from candidature, because I was too young and too inexperienced. When I was ready to throw in the proverbial ‘towel’ , I read a report of the new U.S. immigration bill that had been passed in Congress, which authorized a quota for Ceylon of 100 immigrants each year. I rushed to the American Embassy and submitted my application for a visa. I was told that mine was the first request received, and that in all probability, I would be the first Ceylonese to be legally admitted to the United States for citizenship. I felt like a pioneer, and very proud of myself.

Though the wheels of destiny were in motion, I still had to cover some rough terrain. Not having a sponsor in the U.S., I was required to have with me a substantial sum of money to defray expenses. The knowledge of my father’s sentiments kept me from asking him or my mother for any financial aid. In my hour of need I spoke to my uncles. There were some who could not bear to part with a penny, while others were quite generous. Soon I had added to my savings a small fortune sufficient to carry me through.

I had booked passage on the SS “Orion”. All arrangements had been made, except for a letter from my father authorizing the immigration authorities to issue my passport. I realized that I had a duty to perform, before I ventured any further. I was very much to blame for the animosity created at home. My apology was accepted in good grace, and my father embraced me as the prodigal returned. He knew now how serious I was about going to the United States, and he had no further objections. On the eve of my departure he arranged a gala party. There were as many as two hundred guests. My friends, Americans and local, advised me and wished me well. The party was a tremendous success, and was enjoyed by all.

At dawn the party ended. The guests went their separate ways. We were rather tired, but there was much to do. My relatives and friends helped me to load the trunks in the cars. We rested for awhile, and then in a convoy of cars rushed to the Colombo Harbor. My folks decided to say ‘Goodbye’ at the pier. I embraced them all, and swallowed hard as I saw the tears trickle down their cheeks. The launch put distance between us as it took me to the ship.

The shadows of the evening were about us. The lights of the harbor came on. Soon the loudspeaker sounded ‘Visitors

ashore’, and the friends who came to the ship bade me ‘Goodbye’. The Orion pulled away into the waters of the Indian Ocean, and the bright lights of the port of Colombo faded into memory.

As the “Orion” forged her way through the ocean, I left behind me the sweet memories of delightful ports of call, Aden, Naples, Marseilles and many others. In England I stayed briefly, and sailed on the RMS “Queen Mary” for New York. On this great liner I met many others, who like me, were migrating to the United States. Standing on the deck together, we sighted the famous skyline of New York. The great lady of Liberty guided us with her torch. It was my first glimpse of the real thing. I was in the United States, where the magnificent structures of man challenged the skies, and the nation itself continued in a constant bustle of activity, ever progressing. Here in New York, city of giants, I set my foot upon the land that I would call – home.

My cousin, an itinerant poet, met me, and we rode in a taxi through the streets of a cold, grey New York. Though the air was musty, the breath of the United States was grand. I spent two months in New York touring the largest city in the world. I saw the elegant symmetry of the Empire State Building soaring a mile into the sky. I took in the refinement of Long Island, the jazz of Harlem, and the grime of the Bowery where one could still discern beneath the dirt the remains of a past gay era.

Away from the hustle and bustle of New York, the plane took me to sunny California. To Los Angeles, a romantic city of romantic people. Here too I languished touring the city and her suburbs. I was in glamorous Hollywood where fantasy had become a reality, and reality in turn had become fantasy.

I was finding great joy in my idleness, when it suddenly occurred to me that my finances were rather low. Though the thought was appalling, I had to find a job. The idea of becoming a travelling salesman was appealing and I was soon selling Bibles for a firm in Texas. In a few days I discovered that even the Bible selling business is quite a racket. Unfortunately I was not a very good operator, and had sold only one Bible in the two weeks I had spent at this job. I was discouraged, and so I gave it up.

One day the blue uniform of a U.S. Marine confronted me with my responnsibility to the country that I had adopted. To preserve this way of life a war was being fought in Korea. I had no immediate plans, and only $50.00 in the bank, so I marched through the open doors of a recruiting office into a career as a United States Marine.

With other Americans I endured the gruelling training at boot camp, where I was primarily trained for the defense of the United States. Though I was not placed in a position I had wanted, I was assigned to a rather important phase of Marine combat. I was a supply clerk and an integral part in the nation’s defense. I have pride in my work, knowibg that in a little way I am giving something to the country of my adoption. I have been promoted to the rank of Staff Sergeant, and with the help of the Marine Corps, become a citizen of the United States of America.

The six years I have spent with the Marine Corps have not all been easy years, but they certainly have been good years. I have learned much. The dreams of youth are not all easily forgotten. The dream worthwhile remains. The United States was such a dream, and I became an American.

Note from Rajah’s brother Jayam Rutnam of Los Angeles, Ca.

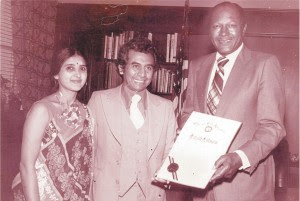

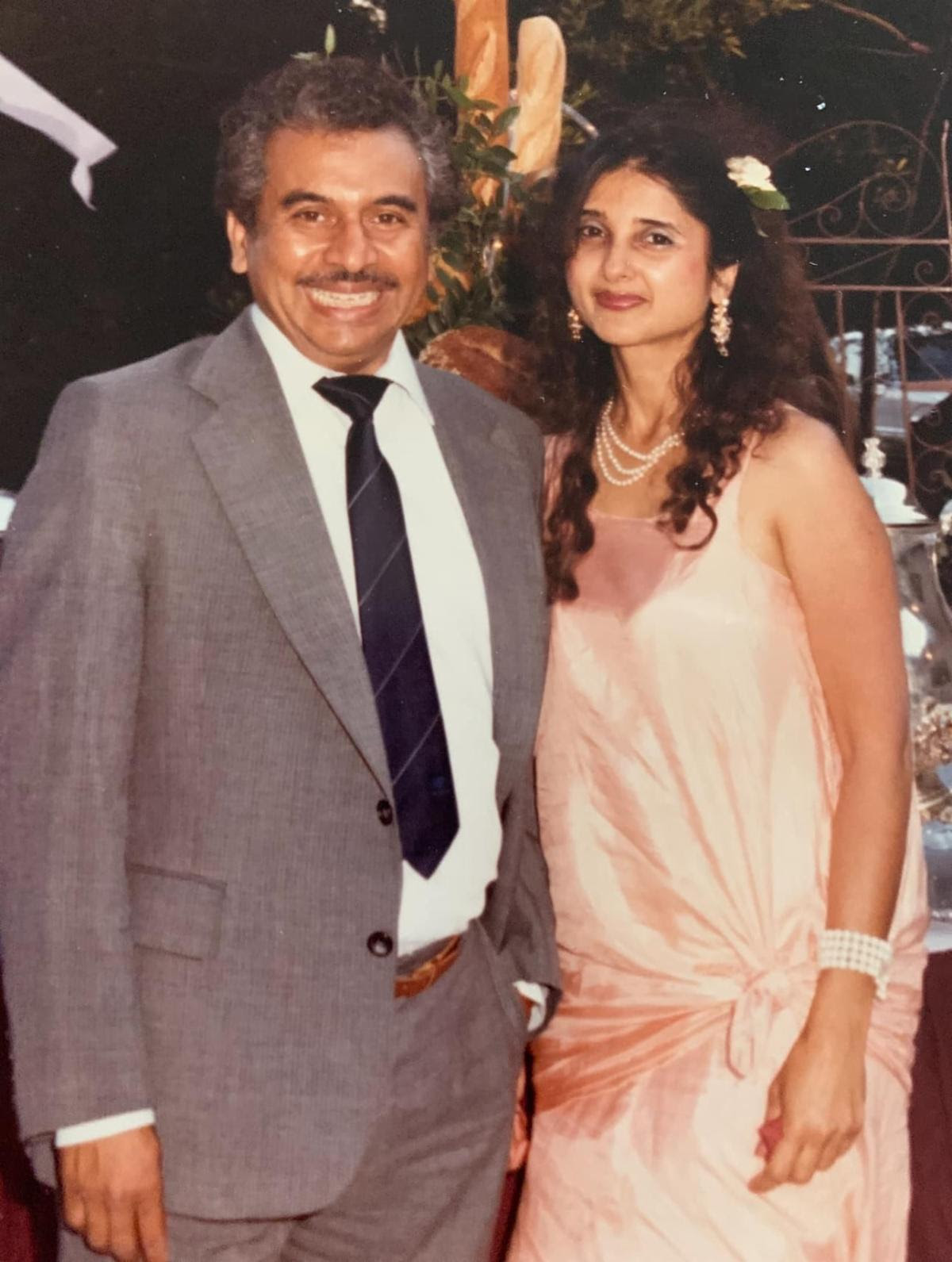

My eldest brother, Rajah, saw his dream come true when he became an American citizen. He spent ten years in the United States Marine Corps, during which time he was promoted to the rank of Staff Sergeant and later retired with an Honorable Discharge. After his military service, he became an executive with a large steamship company in Long Beach.

Rajah married Patsy Bolling, and together they had two children, Vanessa and Dennis André. Upon retiring, he fulfilled another lifelong dream by returning to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where he represented a major garment exporter. He eventually returned to the United States and passed away in 2009 at the age of 75.

Rajah sponsored all his brothers and sisters to come to the United States. He will be remembered as a pioneer, being the first Ceylonese to migrate to the United States under the McCarran Act of 1952.